Blog  Natural Wanders in Australia (Destinations) Blog

Natural Wanders in Australia (Destinations) Blog

Antarctic Beech Forest, Sunset over McPherson Ranges, Regent Bowerbird at Lamington National Park, Queensland, Australia. © Steven David Miller

|

|

|

The Green Behind the Gold (updated from an article for Pacific Way, inhouse magazine of Air New Zealand)

Green Mountains in Lamington National Park towers above Queensland’s Gold Coast and is one of my favorite spots on earth. We return there again and again, drawn by the embracing mountains filled with wildlife. Some of the shyer creatures have retreated to the depths of the rainforest while others seem content to live in peace with the campers in the camping area and visitors to O’Reilly’s Rainforest Retreat (formerly O’Reilly’s Guesthouse). While O’Reilly’s has gone so upmarket it has out-priced many of us who went there for years, the campground has sites set into a hill, offering a priceless view for only a few dollars a night.

We have shared our muesli with birds at the campground and watched marsupial mice madly chasing each other around a bush. We once weathered a thunderstorm that unleashed buckets of rain and cataclysmic thunder and lighting. We have watched sunsets scald the valley below and seen the sun come up over the trees, throwing great beams of light into the hills. On hot summer days we have escaped to the cool rainforest, seeking out waterfalls for relief. We have seen dingoes come to the edge of the trees, peering shyly at us while we ate dinner. There is a pond nearby that sings with the sounds of ecstatic frogs after a heavy rain.

King parrots, crimson rosellas and regent bowerbirds of electrifying colors also flock to the area. Pademelons, bandicoots, possums and sugargliders appear in the evenings and after dark, delighting all who see them. Perhaps the star is the satin bowerbird who builds a bower of thin sticks then paints the walls with berry juice for decoration. To attract a female, he decorates the entrance to his den with an array of blue objects (many of them stolen from campsites). When a female arrives and stands in his bower he performs a little dance for her, picking up his blue treasures and singing to her.

Lamington rings with the sounds of the riflebird, whipbird, catbird, noisy pita bird and Albert’s lyrebird. At night, owls come out to hunt for prey, amongst them the tiny owlet-nightjar that poses on tree branches like a miniature carving.

The flora is also stunning and varied, changing dramatically at different elevations. In the valley below Green Mountains, jacaranda and silky oaks bloom in lavender and orange. Up the mountain road you pass through scrub and eucalypt forest, suddenly entering a tunnel of foliage with treetops rising high above the subtropical rainforest.

Walks from Green Mountains take you further up into the temperate rainforest and the Antarctic beech forest. From there you can gaze out on to the McPherson Ranges undulating in waves of green far into the distance.

These forests contain many surprises such as strangler fig trees, stag horn ferns, lichen, mosses and mushrooms.There is not a square inch of space where something in not growing. On a pathway called Tree Top Walk, a swaying suspended bridge allows a birds-eye view of the forest. From the lookouts you can see flame trees in bloom, blazing like bonfires in the saturated greens of the rainforest canopy.

Step softly through the forest and wonderful things reveal themselves. We once found a diamond python curled up like a loose spring sleeping in a small patch of sunshine, and a pair of yellow robins building a perfect nest. We were entranced by a small scrubwren continually returning to the hollow of a tree trunk to feed its three chicks, each peeping loudly with a gaping mouth the size of a child’s fingertip. A pair of Boobook owls charmed us with their tenderness for each other as they snuggled under a fallen log like two love struck dolls. We have seen dragon lizards sleeping on trees, and tiny skinks peering out from holes in moss covered logs. We have stepped across rushing streams banked with flowering Helmholtzia lily and stood by pools watching the colorful Lamington spiny crayfish dart from hole to hole.

At the southern end of Lamington National Park there is another lodge that attracts its own guests. Binna Burra looks out over a deep valley of thick rainforest and in the distance you can see the Pacific Ocean. They also manage a private campground that includes tent-cabins for families to holiday in. We have camped here in the company of pademelons grazing at our tent door. In the evening, as the sun slips behind the mountains that fall in lavender scoops to the horizon, kookaburras and crimson rosellas glow as they forage for their evening meal. Possums come out later, nibbling on wild fruit and regarding you with soft eyes.

One of the nicest walks at Lamington is a full day trek from O’Reilly’s to Binna Burra (or visa versa) forming part of the Gold Coast Hinterland Great Walk. There is a Saturday morning shuttle that can take you one way, but the truth is, all the walks at Lamington National Park are sublime.

© Linda Lee Rathbun

For more information visit: www.nprsr.qld.gov.au/parks/lamington/index.html, www.oreillys.com.au and www.oreillys.com.au/lamington-national-park/bushwalking/full-day-walks, www.binnaburralodge.com.au

Sunset at Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, South Australia. © Steven David Miller

*For an image of Uluru, please see our March 6th posting below.

Uluru: A Traveler’s Tale (From an article for Nature & Health magazine)

As the road led us closer to Uluru, I thought of our visit there thirty-five years earlier when the Stuart Highway between Port Augusta and Alice Springs was still unpaved. We had approached from the south, turning west to what was then still known as Ayers Rock on a track of choking red dust that turned to pools of sloppy red mud when a rare rainstorm hit. Our first glimpse of the rock was a disappointment: it stood like a gray lump of clay against a black sky with streams of water pouring down it. The campground was not far from the base, right next to the Aboriginal settlement that was a third-world complex of canvas humpies. When the sun finally came out three days later, we felt we had been transported to a different world. The saturated red earth sucked up all the moisture like a massive, dried-up sponge, soon bursting forth with flowers. Dragon lizards and knob-tail geckos came out to bask in the warmth. The sky was a crisp, clear, breathtaking blue. The rock sat like a huge, uncut ruby; a wondrous monolith all the more awesome for the adventure we had been through to see it. After drying out our things that had been wet for days, we set off to explore the rock on foot.

Uluru is a place mystery, and I could feel myself growing solemn as we approached it. As we stumbled across rocks and bushes beneath the towering rock, I was suddenly overcome with a feeling of gloom so profound that I wanted to leave immediately.

“What’s wrong?” Steve asked me.

“Nothing.” Steve knew that “nothing” said like that meant something.

“What is it?” he asked again.

I could not verbalize the feeling I had. It was as if I was walking through a graveyard of bodies that had been buried alive and were screaming to be unearthed. I could not wait to get out of the place. We rushed on, and a few minutes later the feeling vanished. I was able to describe what I had felt to Steve; he had sensed nothing of the sort, so I dismissed it as part of my overactive imagination and we went on.

That evening, we went to the Red Sands Motel for an ice cream. An Aboriginal man was sitting at the bar; he dazzled us with his smile and waved to us, calling us over. We joined him, declining the drinks he offered to buy us. His name was David. He was a teacher from Bathurst Island, his wife was Pitjantjatjara and they were staying with her people at the Aboriginal camp. David kept drinking and spending his money on scratch-off tickets that he bought one after the other, each time hoping with renewed enthusiasm that this would be his lucky ticket. We finally persuaded David to walk us back to the campground, telling him we did not think we could find our way back in the dark (a lie, but we wanted to get him out of the pub). David led us through the bush--a short cut, he claimed, that took us in a very roundabout way to his humpie. He invited us in for a cup of billy tea. As we sat on the dirt floor under a torn piece of canvas that passed as a roof, David asked Steve if he liked music. Steve did.

“Would you like to hear some?” David asked.

Of course we would.

I hoped for something tribal. Something mystical.

“Do you like Conway Twitty or Elvis Presley”, David asked me politely, reaching into a cardboard box to pull out the biggest cassette player I had ever seen. I indicated that I preferred Elvis.

The music was very loud. “It’s now or never, be mine tonight,” Elvis advised us.

An Aboriginal elder came and stood at the open tear of the canvas tarp that served as a door, shouting at David in Pitjantjatjara. He stamped his foot in the dust, pointing a bony finger at Steve and I. David’s wife said something that seemed to calm the man, and with a parting look of disgust, he left.

“That is the Tribal Elder,” David explained. “He forbids his people to drink. Only I,” David added proudly, “am allowed to go to the pub. He thinks you have been giving me grog.”

I was horrified. We were the ones who had dragged David away from the pub. David swapped Elvis for Conway and turned down the music. I decided to tell David about my creepy experience at the rock. He listened, asking where it had happened.

“Near the Kangaroo’s Tail,” I said, referring to a section that was called so by white fellas.

“Oh,” David said solemnly. “That is a sacred place, a place for initiated elders. It is forbidden to women.”

I wondered if I would die.

“Aboriginal women,” David added hastily, after noting the look on my face. “That area is closed to the public; it is fenced off from the road.”

“We weren’t on the road, we didn’t see the fence,” Steve explained. “If we had known, we never would have gone there.”

I reminded myself that I didn’t believe in anything that couldn’t be explained to me logically and scientifically, with plenty of hardcore evidence to back it up. David filled three tin cups with tea so strong you could have stood a spoon up in it, explaining that he couldn’t offer us sugar because the store had run out when the supply truck couldn’t get in because of the rain. David’s wife was cowering timidly in a corner, and though David was a most gracious host, I sensed what a terrible intrusion we were. Steve and I struggled to politely get the tea down with Conway twitting in the background, and camp dogs barking, and a baby crying nearby. It was time to leave, and David insisted on walking us back to our tent in case the dogs took a dislike to us. Our camp was like a palace compared to what David and his wife lived in; we offered him a kilo of sugar which he politely accepted on behalf of his wife’s people. That is so like an Aboriginal; to accept something he is given and then share it with everyone he belongs to.

The next day I was jump roping by my tent, my favored exercise at that time. A number of Aboriginal children came over, and I showed them how to “skip rope”. They were adorable, and kept patting my pockets, saying “lollie, lollie”. I went to the store to buy them some candy, and in there, saw the same tribal elder I had seen at David’s humpie the night before. He had nothing on but a long, dirty T-shirt and a pair of running shorts. The fat, rude white lady at the counter humiliated him by loudly chastising him for not having enough money to pay for the tea he wanted; he thrust out a carving at her in trade, an item she would no doubt sell later to a tea towel-loving tourist at five times the price the elder had received for it. He passed by me, his body held in a disturbing posture of dignified defeat. I was humiliated for him, wondering what his Dreamings were while the fat, rude white lady at the counter probably dreamt of nothing more than sponge cakes and lamingtons. How dare she look down on an initiated, tribal elder, and the traditional owner of the land her shop stood on? We saw David a few more times; he was vastly amused by our version of roughing it when he came to our camp for a cup of tea.

"Ayers Rock" now belongs to the traditional owners, as it should, and it is leased back to the national park service that runs it in cooperation with the owners; it now known as Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. Today, the Aborignal camp is a private settlement, off-limits to visitors. The small village of Yulara caters to all tourist accommodation and needs. The roads are sealed, and it is a well-managed operation. All these years later, after many more trips to that wondrous rock, we still remember David and our first Uluru adventure, an adventure you simply cannot have anymore. We are grateful.

© Linda Lee Rathbun

The Church, Old Ruins, Isle of the Dead at Port Arthur Historic Site, Tasmania, Australia. © Steven David Miller

|

|

|

Exploring Australia’s Convict Past (From the book Natural Wanders in Australia available through Amazon)

Port Arthur is probably Australia’s most significant historic site, its beautiful old ruins stand as a sad testament to the suffering of so many convicts transported to Australia for such minor crimes as stealing a pair of shoes. It sits on the Tasman Peninsula, and there are several scenic spots to stop at along the way. Just before you cross Eaglehawk Neck, linking the Forestier Peninsula with the Tasman Peninsula, is a small historical building: the guardhouse set up to stop runaway convicts from Port Arthur. Any convict who might have made it this far through the dense bushland had to face a gauntlet of armed soldiers and vicious dogs, known as the dog line. A short visit here will become more meaningful once you have been to Port Arthur and learned a bit more about convict history.

Port Arthur has several places to stay, and certainly the most eerie is the Port Arthur Motor Inn, sitting just above the entire convict settlement. Anyone who can walk back up the hill to their room in the dark of the night after a ghost tour, and not wonder if the area is not indeed haunted, has no imagination. We had stayed there on a previous trip, and it is almost unbearably ironic to think we were in these comfortable surroundings while people had suffered here so horribly through the middle of the 1800s. On this trip we stayed at the Port Arthur Caravan Park, an excellent campground and backpacker park with large sites and good facilities.

On the evening of our arrival, we visited Port Arthur to get some night-time photos and to take a ghost tour. Only the church is lit up at night, and there is a spotlight on the old hospital. Other than that, it is dark. Very dark. A ghost tour guide gathers his wards together, and sets off with lanterns to explore the unexplained paranormal occurrences at Port Arthur. Standing in the church, we learned of a gruesome murder where one inmate had hacked another inmate to death with an axe. It was part of a death pact in which prisoners drew straws to see who would murder the other: releasing the victim through homicide, and the murderer through hanging. Suicide was not an option as it condemned one’s immortal soul to hell. Further on, at the vicar’s house, we learned of a minister who showed little mercy to the prisoners, and who continued to haunt the grounds many years after his death. There was the bursar’s house, still haunted by a woman who lost a baby in childbirth. There was the surgeon’s house, where underground dissections on cadavers took place. There was the solitary prison where men where condemned to utter silence, and the essence of despair still lingers in the brick walls. Our guide was excellent, scaring us all profoundly with unexpected bumps in the night.

The next day, we were back at Port Arthur. We wandered around the old pink brick ruins, admiring the gardens, wondering at what sort of life the prisoners had here. A history tour (running at least every hour) gave us a bit more insight. I was fascinated to learn of some of the Canadian prisoners here: political prisoners transported to Australia for their part in the Upper Canada rebellion. For the most part, the men were Irish and British. Close by, was the site of a boys prison where children as young as nine had been sent away for the crime of being street urchins. We spent a while in the museum, another fascinating place to learn more of Port Arthur’s history. As an American, I was intrigued to discover that one of the reasons the Britain began sending its convicts to Australia was that they lost the colonies to the American Revolution and therefore needed new ‘prison’ grounds. Also, it solidified their claim to Australia, and provided free convict labour to the early settlers and the young nation.

The Isle of the Dead is a small island just offshore, and that is where the prisoners (in unmarked graves at the bottom of a hill) and the free people (in marked graves on the rise of the hill) of Port Arthur are buried. We had an afternoon tour there, and once again, the guide was outstanding, lending a sense of drama to the little island. He told us sad tales of prisoners, of guards, of their wives and children. One of the grave diggers out there was a man I’d learned about the night before on the ghost tour. I saw the grave of a child accidentally killed by an incorrect dosage of medicine, the same child who was said to be a ghost haunting the grounds at night. All in all, Port Arthur is a fascinating place. Anyone interested in Australia’s history, or mankind’s inexplicable desire to punish and dominate others, should visit this place.

© Linda Lee Rathbun

*For more information visit www.portarthur.org.au

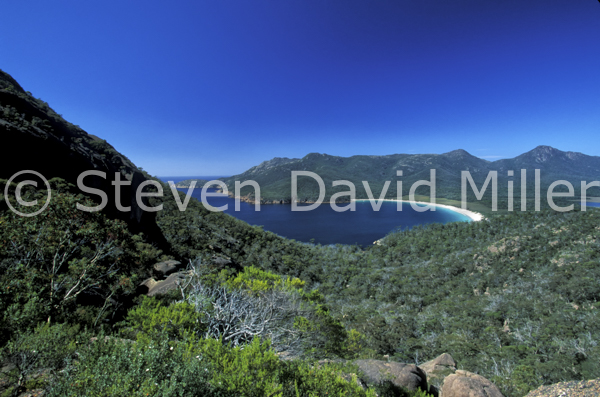

Wineglass Bay Lookout, Scarlet Robin, Wineglass Bay at Freycinet National Park. © Steven David Miller

|

|

|

Exploring Freycinet National Park (From the book, Natural Wanders in Australia available through Amazon)

Along the east coast of Tasmania is an expanse of lonely beaches that extends for many kilometres. About half-way down, just past the little town of Bicheno, is the Freycinet Peninsula. The southern section of this is a national park with pink granite boulders that dominate the landscape like the cast-off toys of giants. The Hazards Range of Mt Mayson, Mt Amos, Mt Dove and Mt Parsons are all cast in granite too, glowing in the light of day. We arrived in the little town of Coles Bay, just outside the national park, late in the afternoon and set about looking for a place to camp, eventually settling on the Big 4 Iluka at Freycinet Caravan Park where we found spacious sites set amongst trees and bushes, and with excellent facilities as well. We selected a site at the top of the hill, looking out over bushland. Bennett’s wallabies roamed about, one with a cute joey in its pouch. A scarlet robin, with intensely contrasting colours of white, black and scarlet, landed in a tree behind our camper. Wattlebirds squawked in the branches, and when it grew dark, pademelons and possums came out to feed. One could not have asked for a more pleasant campsite.

The following morning we woke to a gorgeous day with a cool breeze blowing. It was perfect for hiking, and we organized a lunch so that we could spend the day in the park walking. Without any doubt, the walk to do at Freycinet is Wineglass Bay. It is a steep, rocky climb up to the lookout, but what a view! Below is a beach forming the perfect curve of a wineglass with white sand and aquamarine water. We stood and photographed it for a long while, feeling very lucky we had such a perfect day. For those who don’t have the energy for a long hike down to the beach, it is best to simply return the way you came. However, it would be a shame to miss this beach on a nice day, and we carefully picked our way down the track to finally emerge at the beach. The coarse, ivory sand squeaked under our feet, and just to the north of the bay was a terrace of granite rocks. We sat there for awhile and ate our lunch, hypnotized by the seaweed that swirled like leather ribbons in the water. The air was a bit too crisp for a swim, but plenty of other hearty hikers had brought their bathing suits, and with breathless cries of shock, they plunged into the cold, blue waves.

One can walk to the other end of the beach where there is bush camping and a protected cove, or one can hike across the Isthmus Track to Hazards Beach. We chose the latter, walking single-file through the scrub for about 30 minutes until we reached yet another stunning beach. Here one can hike south to a bush camp (and toilet), or head north back along the Hazards Beach Track. We had done this hike in the past, and I actually found it very boring as you walk through a lot of dense scrub and can’t see the coastline just beyond. However, at Lemana Lookout one can sometimes find a group of wallabies lingering on the rocks, and to see these marsupials gazing out onto the water is rather interesting. We didn’t find them on this day, so we walked back along Isthmus Track to Wineglass, and after a little rest and some chocolate to fortify us, we climbed back up the track to the lookout, and down back to the carpark. This entire hike takes about five hours, but it would be pointless to do it without stopping to enjoy the scenery along the way, so it is best to think of it as at least six hours or more. Freycinet National Park is one of Tasmania’s many, many scenic wonders.

© Linda Lee Rathbun

*For more information visit www.parks.tas.gov.au, and http://www.big4.com.au/caravan-parks/tas/freycinet-east-coast/iluka-on-freycinet-holiday-park.

Ubirr Rock, Yellow Waters Cruise in Kakadu National Park; Florence Falls in Litchfield National Park. © Steven David Miller

|

|

|

|

Kakadu National Park and Litchfield National Park in a Nutshell (From a "Top Ten Destinations" Northern Territory Tourism insert in Caravan World magazine)

Kakadu is a landscape saturated by rivers, which, in the wet season, turn the region into a vast, verdant wetland sprawling beneath soaring escarpments. Tucked into every corner of the park are waterfalls, billabongs throbbing with birdlife and crocodiles, a rich variety of flora and Aboriginal rock art sites painted with the finest examples of x-ray art in the world. The excellent Kakadu Visitor Guide booklet divides the park into regions. At the Mary River end, Gunlom offers lovely Waterfall Creek with a walk to the top of the escarpment. Cooinda has Yellow Waters with a boardwalk and the superb Yellow Waters wetlands cruise. 4WDrivers will not want to miss the road to the Garnamarr Campground followed by a wild track to Jim Jim Falls and a heart-stopping river crossing to Twin Falls. Muirella Park has an evening cultural cruise on Djarradjin Billabong and provides the nearest camping to the stunning rock art at Nourlangie and Nanguluwur. The Bowali Visitor Centre has a wealth of information on every aspect of the park. North of Jabiru is Ubirr Rock with yet more rock art, a view of the Nardab floodplain and the outstanding Guluyambi Cultural Cruise on the East Alligator River. In the South Alligator area, the birdlife at Mamukala Wetlands is prolific. Kakadu is a must-do.

Litchfield is often compared to Kakadu, though its terrain and size are entirely different. The Tabletop Range is carved by spring-fed creeks like the Florence, and sliced open by the Reynolds, the Adelaide and the Finniss Rivers. Campers can base themselves in comfort in Batchelor or at campgrounds in the park, and spend several days exploring Litchfield's many scenic wonders. The sealed road leads to the fascinating Magnetic Termite Mounds. Next are the refreshing swimming holes and natural spas of Buley Rockhole and then Florence Falls. Tolmer Falls is picturesque with a viewing platform and a bushwalk to the top of the falls. Down the winding road to the base of the park is Wangi Falls with a basic caravan campground, a huge swimming hole and a delightful colony of fruit bats.

For the experienced 4WDriver, another day of touring leads to The Lost City with a walk at the end and plenty of birdlife along the way. A more challenging 4WD track, with several fairly deep creek crossings, leads to Blyth Homestead and then on to Sandy Creek Falls. Park your 4WD and take the 3.4km walk bordering a clear creek to the perfect falls and grotto for a picnic lunch and a swim. Litchfield's swimming holes are all croc-free, something Kakadu can never lay claim to!

© Linda Lee Rathbun

*For more information visit www.kakadu.com.au- and www.parksandwildlife.nt.gov.au/parks/find/litchfield-

Uluru at Sunset, Kata Tjuta at Sunset in Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park; Kings Canyon Rim Walk at Watarrka National Park. © Steven David Miller

|

|

|

Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park and Watarrka National Park in a Nutshell (From a "Top Ten Destinations" Northern Territory Tourism insert in Caravan World magazine).

Uluru draws visitors from around the globe like a giant, red magnet with mystical properties. Few people can stand before that rock, bathed in the scarlet glow of sunrise or sunset, and not be moved by its inner power. The township of Yulara caters expertly to everyone including campers, and if the budget permits, the Sounds of Silence al fresco dining experience on a clear night is a memorable treat. For the best view of Uluru's remarkable light show at dusk, head to the sunset viewing area with a platter of nibbles and a glass of wine to toast Mother Nature's most awesome structure.

During the day, the Cultural Centre offers tours and an insight into the deep, spiritual meaning of the rock for the Anangu people. A self-guided walk around the base of Uluru makes for a delightful morning or afternoon. And then there is Kata Tjuta, sitting in the distance like giant scoops of purple prehistory. Watch for wild camels on the drive out there, and spend an outstanding afternoon doing the Valley of the Winds Walk through the rounded, sacred mounds. For a fiery sunset equal to that at Uluru, go to the Sunset Viewing and Picnic Area and stand in awe as the domes light up with a fire from within.

It would be a shame to drive all the way to Uluru and not take an extra few days to visit Kings Canyon, now known as Watarrka National Park. There is no camping in the park; the nearest place for campers is Kings Canyon Resort. If a couple should happen to be there on their anniversary, then the resort's Under a Desert Moon dining experience might be a nice way to celebrate. Sunset sees all visitors facing the George Gill Range for a fiery show.

It is the daytime though that shows Witarrka at its best. Kathleen Springs has a wildflower-banked walking track to a petite, pretty spring. Another charming short walk is in the basin of Kings Canyon itself: this is a meander along Kings Creek with views of the canyon rim up above. For one of the best walks anyone could hope to do in a lifetime of walks, the 6km Kings Canyon Rim loop is superb. Pack a hearty lunch and get an early start to beat the soaring mid-day temperatures. The initial, steep climb up onto the rim is breathtaking in more ways than one; from then on, the only thing to constantly take your breath away is the scenery.

© Linda Lee Rathbun

For more information visit www.environment.gov.au/parks/uluru-, www.ayersrockresort.com.au-, www.parksandwildlife.nt.gov.au/parks/find/watarrka-, www.kingscanyonresort.com.au-

Ballroom Forest Walk, Cradle Mountain & Dove Lake, Crater Falls. © Steven David Miller

|

|

|

Cradle Mountain Lullaby (Drawn from articles for The Weekend Australian, Views, Boca Raton, Qantas, Nature & Health magazines and Natural Wanders in Australia available through Amazon.)

Tassie, as Tasmania is affectionately called by the Aussies, has a rich colonial history, and has almost one-third of its land mass set aside as wilderness. The most accessible of this protected region is Cradle Mountain-Lake St.Clair National Park, pinned into the northwest section of Tasmania’s rugged, pristine wilderness region that includes three other world heritage national parks (Franklin-Gordon Wild Rivers N.P., Southwest N.P. and Walls of Jerusalem N.P). Cradle Mountain itself is a craggy zenith lurking above the waters of Lake Dove and surrounded by alpine meadows and temperate rainforests, the view of that mountain reflected in the deep blue waters of the lake has to be one of the best in the world. This entire park is formidably beautiful with savagely unpredictable weather and bushwalking that will put blisters on your toes and a song in your heart.

There are several lovely walks near Cradle Mountain Lodge, a spectacular place to stay, though having said that, we usually camp at the Cradle Mountain campground. My favorite lodge trails include the Enchanted Walk (which can also be accessed from the national park visitor centre) where you walk through an enchanted forest, the Pencil Pine Track bordering the enraged river of the same name and the King Billy Track which should only be attempted when the ground is dry. However the best walks are within the park. There is the picturesque Dove Lake Loop Track with an essential detour to the Ballroom Forest, or more challenging hikes to Marion’s Lookout via Crater Falls and Crater Lake. These are at the start of the Overland Track, a five to six day backpacking journey that bisects the park and delivers walkers to Lake St. Clair. This track can be hell or heaven depending on the weather; there are huts along the way, but you must carry a tent in case they are full. A few companies offer a guided track with their own private cabins (that means hot showers and hearty meals) for those who like their wilderness with a side of comfort. Most of the walks at Cradle Mountain are half-day or full-day, and all have scenery and inclines that will take your breath away. Be sure to stop at the Waldheim Chalet, a backpacker’s hut run by the Lodge for the national park service. From there, the Weindorfers Forest Walk is simply mandatory.

It isn’t just about the walks though because the park’s wildlife is stupendous, and with most species being nocturnal, evening is the time to go in search of critters. Mountain brushtail possums emerge from their daytime hiding places to forage for food. Pademelons, a tiny species of kangaroo, step shyly across carpeted meadows and soft forest floors. Bennett’s wallabies linger in the last light of day, munching shyly on greenry. Tasmanian devils and spotted quolls can also be seen, but they seem to come out a bit later. One of the best memories of my entire life is sitting on a hillside above a massive warren of wombat burrows. A baby wombat kept popping out of an entrance, and if we sat as still as statues, it would come out to gallop around us like a joyful puppy. Cradle Mountain: simply put, it is a lullaby for the spirit.

© Linda Lee Rathbun

*For more information visit www.parks.tas.gov.au-, www.cradlemountainlodge.com.au-, www.big4.com.au-. (cradle mountain)

Lagoon, Ball's Pyramid, McCulloghs Anemonefish at Lord Howe Island, New South Wales, Australia. © Steven David Miller

|

|

|

|

Lord Howe Island (Drawn from articles for Australian Wellbeing, Sport Diving, Australian House & Garden magazines and Natural Wanders in Australia available through Amazon)

Lying between Australia and New Zealand is that lonely stretch of Pacific Ocean known as the Tasman Sea. Suddenly, from the depths of a submerged mountain range known as the Lord Howe Rise, the remnants of an ancient shield volcano rise abruptly through the surface of the water to form a crescent of land. This is Lord Howe Island, a curving slice of uncut jade melting into a swirl of liquid blue crystal. It is a small subtropical gem that sparkles with an abundance of unique wonders.

To begin with, the last thing you would expect to find this far south is a coral reef. At this temperate latitude there aren’t any, anywhere else on earth. Yet here is an island fringed by a dazzling necklace of over 90 coral species and decorated with those neon colored fish that you normally find on the Great Barrier Reef. Lord Howe is bathed in a cocktail of equatorial and temperate currents, each bringing an assortment of fish and invertebrate life that makes for the most unlikely of integrated aquatic neighborhoods. The land flora and fauna are also unique, evolved over six million years in isolation.

The island is instantly captivating. At the center is a billowing verdant quilt of dense forests and lush clearings. To the north the hills scoop upward, then plunge abruptly into the sea. A long sliver of sand spills into a sapphire and aquamarine lagoon, forming the reef-fringed west coast. Beaches, bays, cliffs and promontories bite wedges into the east coast, creating a jagged line. To the south the island changes shape. The ascending incline of Mount Lidgbird rises into a colossal wall of basalt rock that forms a virtually inaccessible tower of 777 meters. It then falls and rises again to the twin peak of Mount Gower, which in turn drops like the wall of a citadel straight into the ocean. These two peaks are almost always covered in cloud, lying over them like a white shroud hiding the secret castles of mythological gods.

It is impossible not to fall in love with Lord Howe. The island, ravishing from end to end, is only twelve kilometers long and a few kilometers wide. The only road, partly shaded by a canopy of trees, runs along the west side. There are cars, but most people get around on motor scooters or bicycles. Lord Howe has been a magnet for visitors for many yeas. Scientific expeditions have found endless reasons to visit: conchologists looking for mollusks and paleontologists searching for fossilized Meiolania platyceps, a long gone horned turtle. Even the Air Force has an excuse to visit, they like to practice short landings and take offs on the 1,000-meter runway in those huge Hercules airplanes. People used to come by ship, then by Catalina and Sandringham flying boats, now by plane. One visit to Lord Howe never seems to be enough; some people I have met there had been coming out regularly over the past six decades.

The birds of Lord Howe are bewitching. Sacred kingfishers decorate the branches of trees like rainbow ornaments. Golden whistlers serenade each other with songs that sparkle. Emerald doves murmur soft worried calls that blend with the sea breeze. Red-tailed tropicbirds soar in the updraft of Malabar Cliff. On a walk to the south end I once met a few of the Lord Howe woodhens, a bird that came as close to joining the dodo as any creature dares to get.

Even more abundant than the bird life above is the animated marine life bursting below. Fishermen catch kingfish by the boatload and at Pinetrees, where I have stayed, this is frequently on the menu in a creative range of recipes, all of them delicious. The diving on Lord Howe is kaleidoscopic. Tropical corals grow alongside calcareous algaes in unusual gardens of color. In the lagoon, green turtles feed on sea grass. I met one so tame it allowed me to swim beside it while it stopped to gobble food, as though it thought we had a date to dine together. Huge butterfly cod, their spines fluttering about them like swirling flamenco skirts, gather under ledges in groups of five or six. Off Ned’s Beach, on the eastern coast, more coral grows in sprawling clusters that gild the seabed. A merry-go-round of trevally and spangled emperors circle around swimmers reflecting more silver light than a mirror ball in a discotheque. The fish are so used to being fed by islanders and guests that they follow snorkellers and divers around like over zealous dive buddies. Moon wrasse and parrotfish scorch past in a blaze of colors. A small moray eel slithers through a network of tunnels and holes. McCulloch’s anemonefish, endemic to Lord Howe, flourish in the sensuous tentacles of swaying anemones. This is an aquatic Eden, a perfect place to end each day in a Technicolor dream.

Aside from bird watching and diving, I have enjoyed many a walk through the subtropical rainforests that cover the permanent preserve areas of Lord Howe. About one third of the island’s several hundred species of plants are endemic. There are many kilometers of walking trails cutting through the forests, most of them ending with yet another stunning vista. Lord Howe comes as close to being a paradise on earth as any place I’ve ever visited.

© Linda Lee Rathbun

*For more information on Lord Howe Island, please visit www.lordhoweisland.info- and http://www.visitnsw.com/destinations/lord-howe-island-.